Chemical Shift

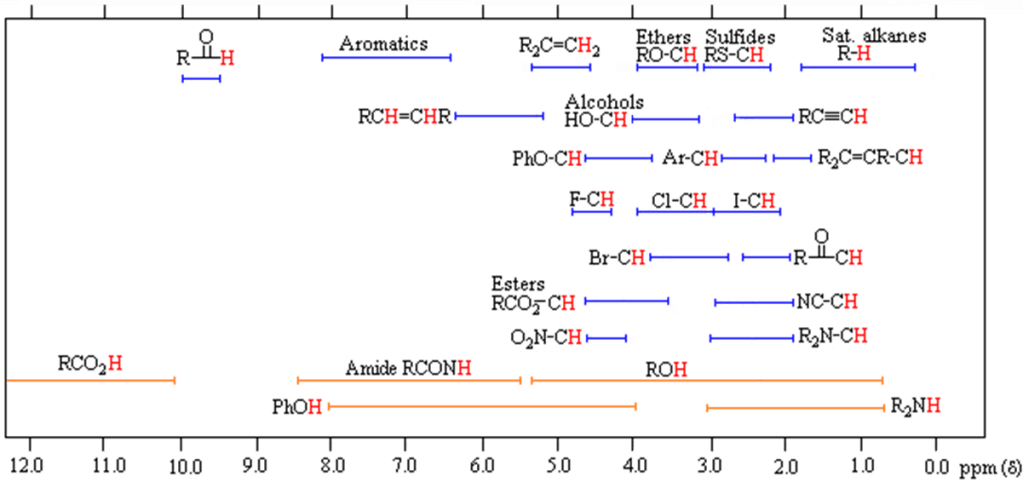

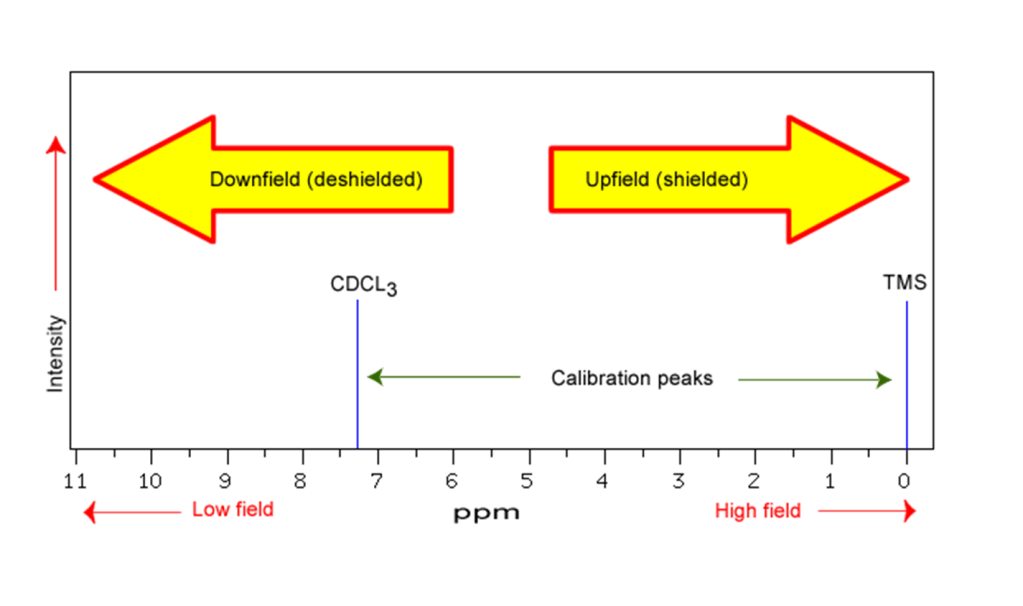

The Chemical Shift is the position in the spectrum of the peak in ppm. This is the resonance frequency of the nucleus relative to a standard in the same magnetic field. The chemical shift is affected by the local chemical environment of the nuclei with different chemical groups having specific chemical shift ranges. Here the chemical shift ranges for protons within various functional groups are shown

The chemical shift of an individual nucleus will depend on a number of factors primarily shielding/deshielding of the nucleus from the magnetic field due to electronegativity, anisotropy and hydrogen bonds.

Shielding/deshielding

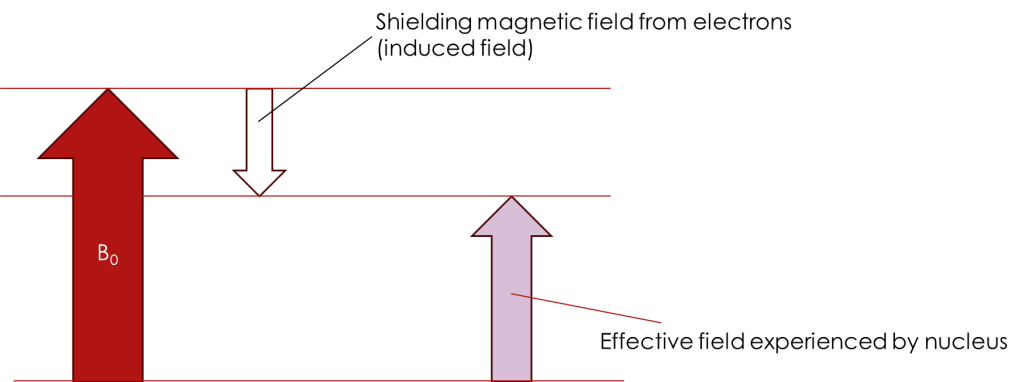

Valence electrons around the carbon circulate in response to the magnetic field B0. The Circulating electrons generate their own magnetic field that opposes B0. This induced field shields the protons, by a small but significant amount, from the full effect of B0. Thus, the effective field the protons experience is weaker than B0 resulting in a lower resonance frequency.

Deshielding is due the the withdrawal of electrons from around a nucleus so that it experiences much greater effect of the B0 field than if the electron were present. The effect on chemical shift is that nuclei that are shielded are seen in the spectrum at higher field (lower ppm) and those that are deshielded occur at lower fields (higher ppm).

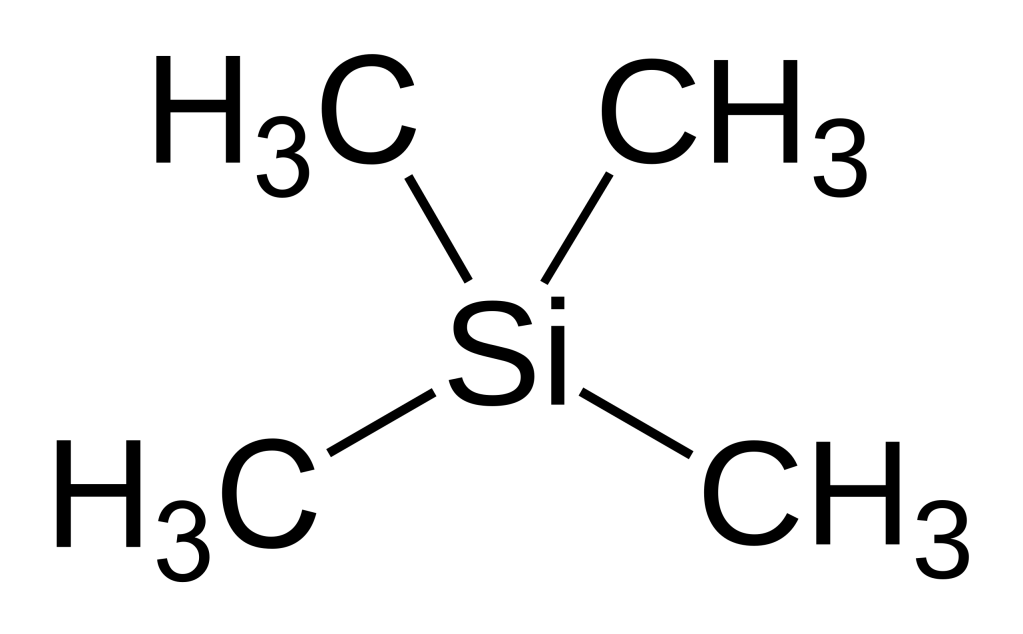

Protons in TMS are highly shielded. Silicon is less electronegative than Carbon. Silicon therefore donates some shielding electron density to the carbons which in turn donate this to the protons resulting in the chemical shift of TMS to be 0 ppm.

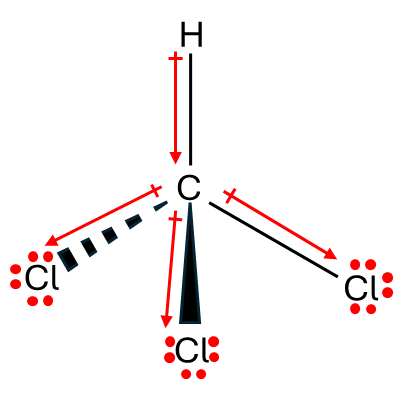

The chlorine nucleus is highly electronegative and pulls in electrons to itself away from the carbon and in turn the protons. This results in the deshielding of the proton within the chloroform molecule.

Anisotropy and Chemical Shift

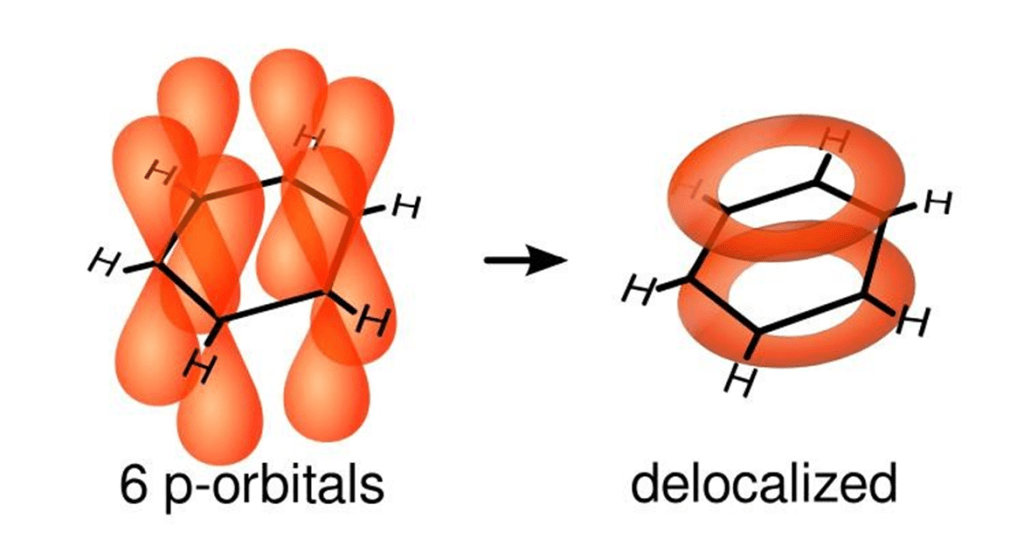

Some protons resonate much further downfield or upfield than would be expected if we consider only electronegativity. Examples for this include aromatic protons which appear at a much higher frequency than can be explained by electronegativity

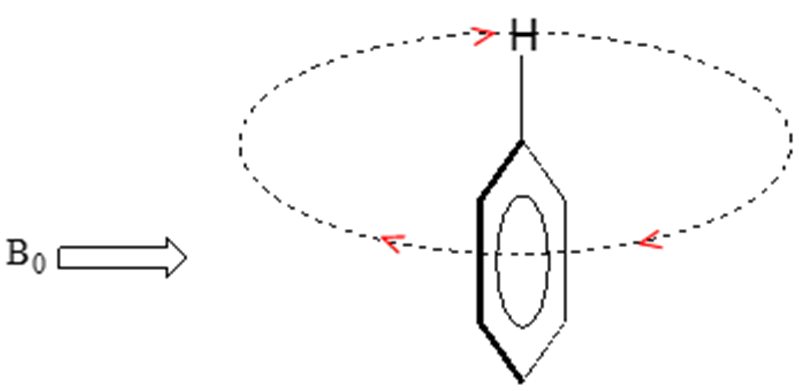

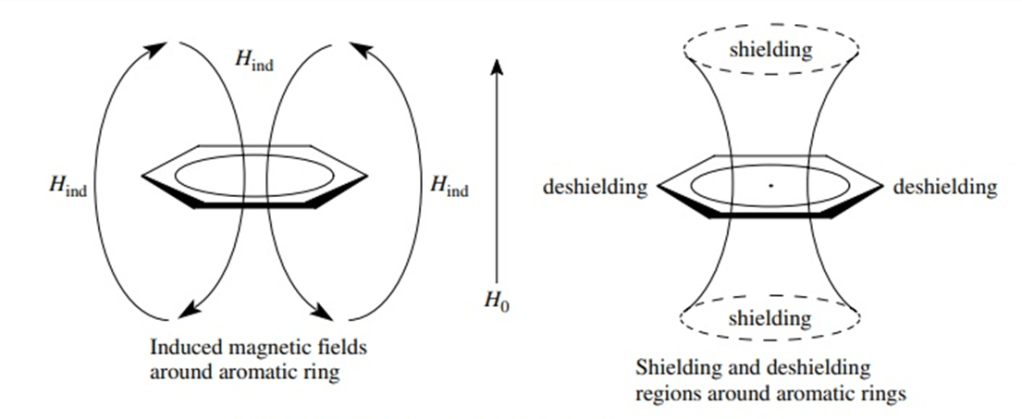

The delocalised p-electrons of an aromatic ring begin to circulate when exposed to a B0 field. This creates a ring current which generates an induced magnetic field that opposes B0. However, this induced field causes the protons to experience a stronger magnetic field rather than shielding them from B0.

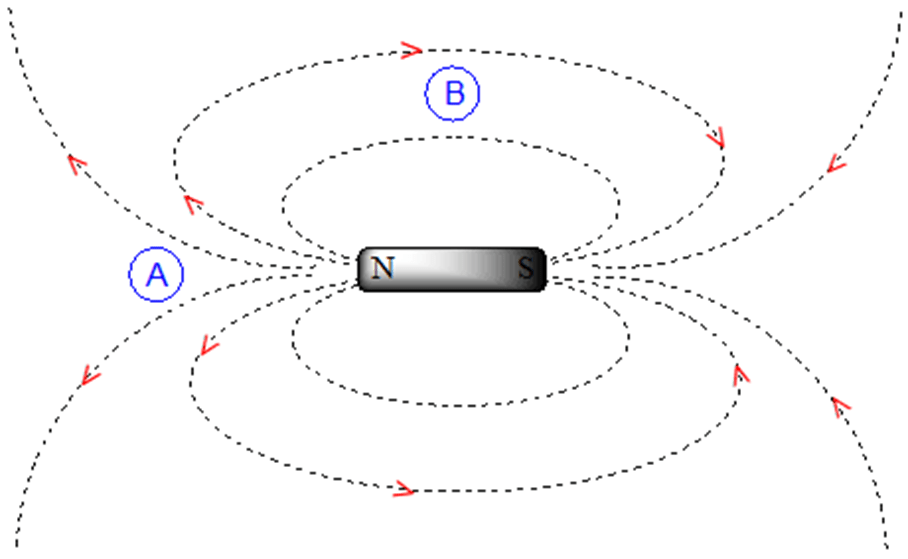

Magnetic fields are not uniform but are anisotropic. If we are at point A we experience a magnetic field pointing North. If we are at point B we experience a magnetic field pointing South.

In an aromatic ring, the protons are at the equivalent of point B resulting in the induced field being in the same direction as the applied field B0.

Aromatic protons are subjected to three magnetic fields: the applied field (B0), the induced field from the non-aromatic electrons (giving a shielding effect) and the induced field from the p-electrons pointing in the same direction as the B0 field. The result is that aromatic protons appear to be highly deshielded resonating in the range of 6.5-8 ppm.

Shielding and deshielding zones

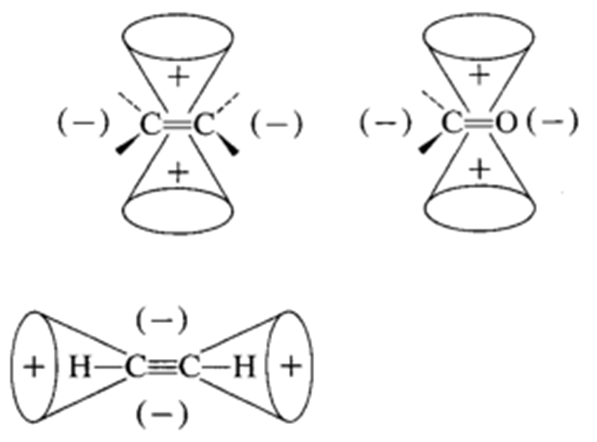

For a double bond the ends are deshielded and the region above and below the double bond are shielded. For triple bonds the reverse is true with the ends being shielded and the regions above and below being deshielded.

In aromatic rings we have seen that the aromatic protons that lie in the plane of the aromatic ring are deshielded. The regions above and below the aromatic ring are shielded. This is especially apparent in proteins where the very high field methyl groups (< 0 ppm) tend to be found in the hydrophobic core of the protein, close to an aromatic ring, but unlike the aromatic protons they are positioned in the shielded region.

Previous: Nuclear Precession and Signal Generation

Next: J-Coupling